Murals and Misunderstandings

‘To make a mural,’ the Mexican artist Diego Rivera once said, ‘is to put the world on a wall.’ Britain, however, has long been uncertain which world it wishes to reveal. In the 1920s and 1930s, the nation briefly imagined its public spaces could hold images of enduring purpose, a vision which ultimately ended with the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Artists secured mural commissions through a variety of channels, though competitions were often the preferred mechanism, particularly for public or memorial works. Local authorities, memorial committees and later the Arts Council would invite designs, allowing architects and officials to select schemes that suited their civic ambitions.

Elsewhere, architects simply turned to artists they trusted, keen to achieve a harmonious marriage of painting and building. It was, in short, a system in which public virtue and private taste each played their part.

Artists including Mary Adshead, Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden, William Roberts and Gilbert Spencer were entrusted with decorative schemes for schools, colleges, government buildings and pavilions, in an era that took the visual dignity of public life rather more seriously than ours does; it is a period to look back at with admiration and disbelief.

The tragedy, of course, is that the murals themselves have fared little better than the idealism behind them. Many have vanished with a briskness that would impress a Soviet archivist. Changing building use has obscured them; layers of municipal magnolia gloss has smothered them.

Of course there were the wartime losses. In 1938, Sir William Rothenstein stood before Charles Mahoney’s Morley College murals in its Westminster Bridge Road building and declared them ‘the finest in this country since Ford Madox Brown adorned Manchester Town Hall.’ Max Beerbohm, he recalled, became positively enraged that the murals, painted in 1930 were not thronged with admirers. Two years later, on 15th October 1940, all were rubble when Morley College suffered a direct hit from a German bomb . The companion works by Bawden, Ravilious and John Anthony Greene, to say nothing of the 57 people who perished alongside them.

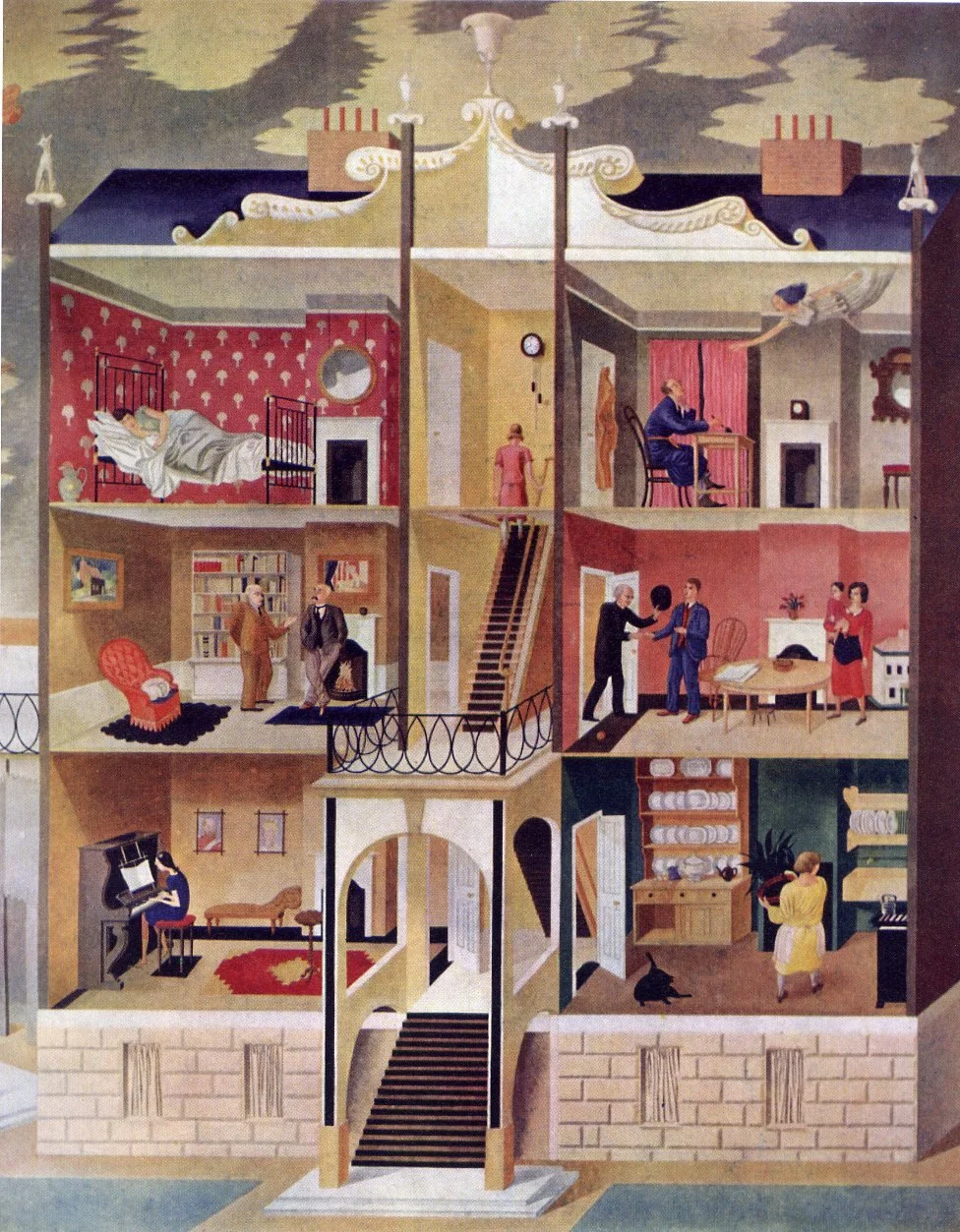

‘Life in a Boarding House,’ (c1930) by Eric Ravilious for Morley College

The best muralists have always understood the demands of architecture, the discipline of large surfaces, and the necessity of clarity and rhythm from a distance. Standards in mural painting were high because commissions were scarce and competition fierce; today, by contrast, the ease with which anyone can apply paint to a wall has sometimes been confused with an ability to create a design worth looking at.

Out of the desolation of the Second World War emerged a host of proposals for a national celebration of renewal, proposals that eventually coalesced into the Festival of Britain. Although the idea drew on many contributions, its political champion was Herbert Morrison. As Leader of the House of Commons in Attlee’s government, he drove the project forward, insisting: ‘we ought to do something jolly… we need something to give Britain a lift’

The Festival would open in 1951, the year of the general election. The Festival committee commissioned an extraordinary range of murals: from Keith Vaughan’s dramatic vision of Theseus raising a torch among explorers, to Edward Bawden’s remarkable Country Life in Britain, a vast concertinaed exploration painted with rural crafts, country houses, pubs, wildlife, and village life. At 47 feet high by 36 feet wide, it was among the largest mural commissions of its time.

The Festival opened on 3 May 1951 and drew huge crowds to the South Bank. Although there were hopes of extending the pageantry beyond its original September closing date, the decision not to extend it had already been taken three months earlier under Labour, with a Demolition Working Party instructed to clear the site by the end of the year.

The London County Council, which owned the land and had long harboured ambitions to develop the area into a lasting cultural quarter (as evidenced by the Royal Festival Hall), had no intention of preserving the Festival in aspic though it envisioned measured redevelopment rather than ceremonial annihilation. Yet when the Churchill government came in that October, they embraced the demolition process with far greater gusto, sweeping away the Festival’s icons with a vigour that suggested not merely tidying up temporary structures but purging a visible emblem of Attlee-era optimism. Thus the bulldozing of the pavilions began with the Dome of Discovery in 1952, and so too did the obliteration of its modernist murals, as if the new administration could not endure even the memory of its predecessor’s architectural exuberance.

Bawden’s mural was dismantled and initially stored by the Ministry of Works at their warehouse at Barry Road in London. Over the following decade the panels were kept in conditions that were never properly documented, and we don’t know what state they were in by the end of this period—whether they had deteriorated, been damaged, or remained intact. When the warehouse itself was demolished a decade or so later, the mural panels are thought to have suffered much the same fate. An internal memo written in 1961 by a Treasury official said of Bawden’s work: ‘Its decorative value is a matter of opinion, and it is not considered saleable for any other purpose, or even as firewood.’

‘Country Life in Britain,’ (1951) by Edward Bawden

The fate of other significant commissions underlines both the fragility and the value of the surviving works. John Piper’s forty-two panelled ‘The Englishman’s Home,’ was re-discovered and acquired by the Rothschild Foundation in December 2022. There are plans to show the mural in its entirety, a small number of its panels plus a pair of murals by Edward Bawden are already on show in the Stables café at Waddesdon Manor.

Though not connected with the Festival of Britain, pieces from another well-known mural have come to light. In early 1928, Lord Beaverbrook commissioned the artist Mary Adshead to produce a mural for the dining room of Calvin Lodge, his Newmarket home. The resulting work, An English Holiday, was to portray scenes of local life, including the local racecourse and to feature portraits of his friends and acquaintances, among them Winston Churchill and Arnold Bennett on their way to the stands; yet, despite its ambition, the mural was never fully installed.

Lady Diana Cooper, with her usual social acuity, is said to have taken Beaverbrook aside and urged him to reconsider. Accepting the murals, she pointed out, would condemn him to dine each evening looking at his friends and allies, a prospect that could become awkward should he fall out with any of them, as he was apt to do.

Beaverbrook, sensing the difficulties, agreed. The commission was cancelled, Adshead received a two-thirds rejection fee and what followed was the fate of many decorative ventures once divorced from their intended setting.

‘An English Holiday, The Puncture,’ (1928) by Mary Adshead for Lord Beaverbrook

The panels lingered with Adshead for a time before slipping quietly into the currents of the art market. A few were sold, others found their way into private hands, and the rest drifted into that half-shadow frequented by orphaned works of twentieth-century muralism. Now and again one reappears at an auction, a reminder of an ambitious scheme undone by a well-timed whisper over dinner.

We may be a country which is careless with its murals, but we rarely succeed in destroying every last trace of them, a fact not lost on the art historian and archaeologist Eugenie Strong who saw this danger more than a century ago.

Writing to The Times in 1923, she pleaded for the systematic recording of Britain’s murals before they were lost for good. Her appeal was treated with that British mixture of courteous interest and inaction.

A century after Strong’s plea, a national effort is finally under way. Art UK has begun a comprehensive study to record murals across Britain, an attempt to create the systematic survey that earlier generations never achieved. The project acknowledges that murals require documentation as much as conservation, and that the first step towards valuing them is simply knowing where they are.

If the Festival of Britain represented murals at their most ambitious, contemporary public art represents them at their most disposable.

No figure embodies this shift more visibly than Banksy, the world’s best-known street artist, whose presence looms so large over the landscape of modern muralism that he has become, for many, its entire definition. Banksy crashed onto the art scene in 1999 with The Mild Mild West which shows a teddy bear about to throw a Molotov cocktail at three riot-police officers, a reference to tensions between police and youth in Bristol earlier that year.

His popularity arises precisely from the absence of traditional artistic depth in his work. Real art is elusive, complex, ambiguous and invariably difficult. What Banksy offers is immediacy: we know we are getting, it is an instant readable picture, perfectly suited to the Instagram generation.

‘Sweep it Under the Carpet,’ (2006) by Banksy at Chalk Farm Road, London.

Banksy’s ubiquity has encouraged the modern belief that anything sprayed onto a wall is, by definition, public art. Today, city and town centres are littered with creative interventions,’ community projects, and street-art makeovers. The emphasis is no longer on harmony with surrounding buildings but whatever looks good on a council Instagram feed.

Epsom and Ewell Borough Council in Surrey illustrates this perfectly. After reports of antisocial behaviour—including robbery and sexual assault—along the route between Nescot College and Ewell East station, the local Community Safety Partnership enlisted young people to brighten up and claim ownership of the underpass.

By what logic spray-painting the bridge mauve and adding stylised robins and blue tits will deter a would-be mugger remains unclear. Some locals say the tunnel now feels even more ominous, Not long ago, graffiti was a furtive act committed after dark and classified as criminal damage; now it’s seen as cultural renewal.

The mural at Ewell East tunnel (2025)

The key issue is what we stand to lose. The remaining works of the last century shows what can happen when standards of quality and seriousness are expected. That era assumed that public art should demonstrate craft, technical skill, and a belief that public spaces deserve ambition. Their gradual disappearance shows the consequences of treating art as decoration. The rediscovery of lost murals suggests that art survives when we value it. If public art were treated as a responsibility rather than a finishing detail, we might stop painting over what was made for us and encourage new work that stands alongside the best of the last century.

Is it unrealistic to hope for the standards exhibited at the Festival of Britain to return? Not necessarily. Public taste can recover. Cultural expectations can rise. Until then, we remain a nation that once commissioned work of imagination and beauty and now congratulates itself on a graffitied bridge. The comparison is not flattering and a lot of people genuinely can’t tell the difference between trained technique and amateur work, so they assume the difference isn’t real. The mystery is why this needs saying but that it does, is an attitude unmistakably of our age.

Richard Morris